How the Boks felled the resilient Welsh

The quarter-finals of the Rugby World Cup kicked off in glorious fashion on Saturday, as South Africa and Wales fought out an enthralling contest at Twickenham.

The two-time winners of the competition, the Springboks, came out on top at the conclusion, defeating Wales 23-19, but it was competitive throughout and bore just as much resemblance to a boxing bout as it did to a rugby match.

It wasn’t the Rumble in the Jungle or the Thrilla in Manilla, but it had all the hallmarks of box office heavyweight clash.

The Welsh came out as the heavy sluggers, looking to land knockout blows early, only for the Boks to bob and weave out of harm’s way, playing the role of the archetypal counter-puncher. As the hooks and straights of Wales began to tell on the home nation’s energy reserves, the South African’s began to exert control of the ring, biding their time and searching for the decisive haymaker.

If Wales were Sonny Liston, George Foreman or Joe Frazier, then South Africa were every inch Muhammad Ali.

Rounds one through three, Wales

Wales started hard and fast, throwing nice combinations and hurting the Boks. They even came close to having South Africa on the ropes, only for them to then clinch and lose any advantage they had worked so hard to gain.

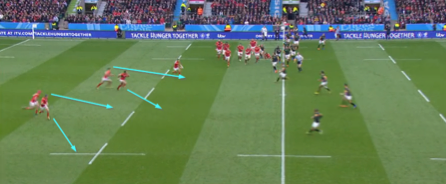

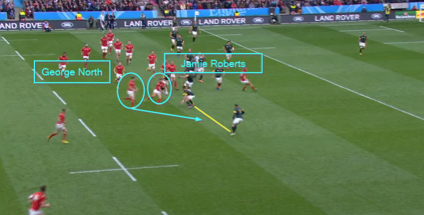

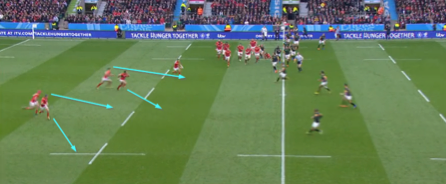

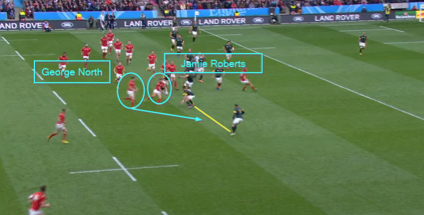

Off of a lineout just a minute into the game, Dan Biggar tried his now trademark up and under. With the Welsh backs running from deep (George North and Tyler Morgan straight, Jamie Roberts and Alex Cuthbert on wider angles), it looked for all money as if Biggar would use them, but he instead went to the boot, catching South Africa flat-footed.

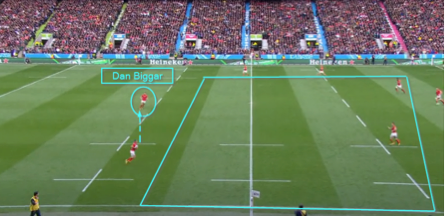

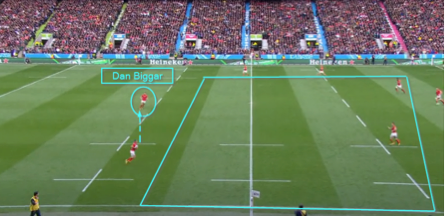

Biggar managed to find grass in the middle of the pitch, an area which Willie le Roux or Fourie du Preez should have had better covered, and though Wales weren’t quite able to get there in time and challenge for the ball, it exposed a weakness in the South African defence.

Poor discipline cost the Welsh three penalties and nine points over the next 15 minutes, but their attacking work rate was rewarded shortly after when Gareth Davies crossed for his fifth try of the tournament.

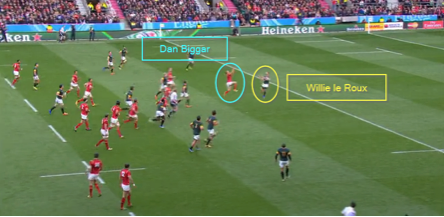

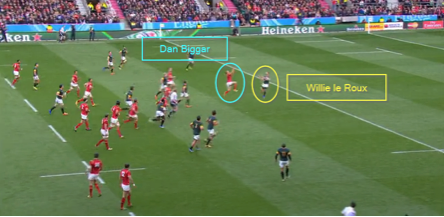

South Africa cleared their lines with a long kick out to Gareth Anscombe on Wales’ right wing. The full-back quickly passed the ball back in-field to the waiting Biggar and the fly-half was faced with at least 25m of space in front of him, with no sign of a South African kick chase.

The fly-half took the ball to the halfway line before unleashing another of his precision up and unders and put himself in one-on-one competition with le Roux. Apart from one quick glance ahead to see what he may be faced with after collecting the kick, Biggar never took his eyes off the ball. He timed it to perfection and was rising to meet the ball before le Roux had even properly arrived in the vicinity.

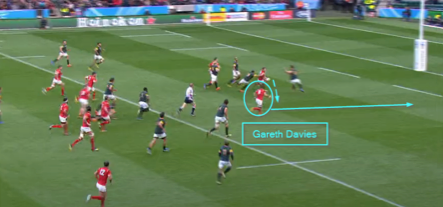

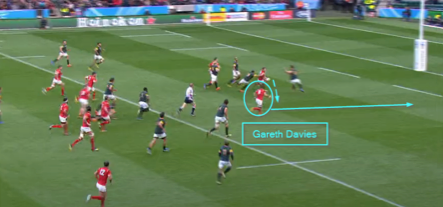

Biggar may have left le Roux red-faced, but his work wasn’t done. The South African cover defence was alert and had two men on hand to stop Biggar from having an easy run through under the posts. Fortunately for the fly-half, his half-back partner was on hand with the support and was able to cruise over the try line after Biggar had drawn the last defenders and made a composed pass.

Rounds four through eleven, split points

As the game progressed, momentum began to swing between the two sides. Neither side was able to penetrate the guard of the other, keeping their hands high and their heads moving. If one thing was notable however, it was that South Africa were starting to take control of the ring, keeping Wales on the back foot, and beginning to establish their range with jabs.

Both sides struggled to clear out defenders at the contact area, either allowing possession to be stolen or giving up regular penalties for holding on. Wales were particularly culpable in this facet, with Springboks forwards and backs alike wreaking havoc at the breakdown.

It’s a cardinal sin in rugby to be turned over on first phase ball, as your support should be in position to clear out any defensive attempt to steal the ball, but that is exactly what Wales gave up from a lineout midway through the first half.

Coming off the lineout, Roberts drew his man and created a hole for the supporting North to run through.

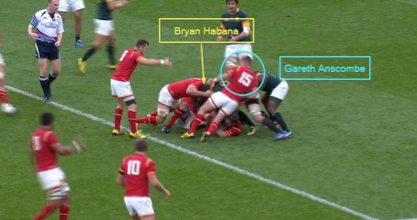

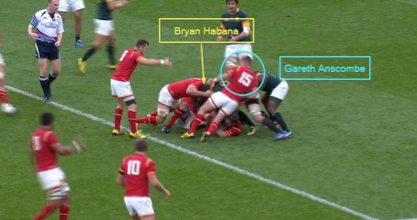

North actually exposed the gap between Jesse Kriel and Bryan Habana well, but ultimately it led him down a blind alley and to a Habana turnover, rather than to the wider channels where Wales would have had a two-on-one with le Roux.

The turnover was actually won by Habana, who is latched onto the ball out of view, but Anscombe’s (poor) attempted clear-out on Francois Louw is representative of the struggles endured by Wales in this area all game long.

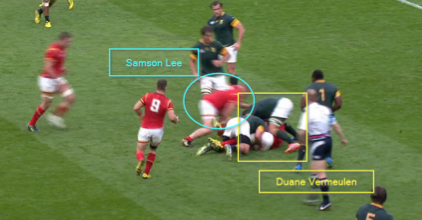

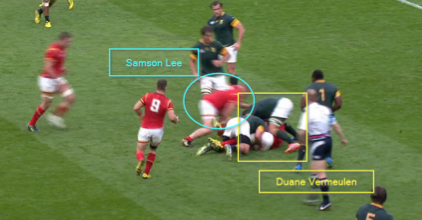

Again, just minutes later, you can see Wales struggle to disrupt the fetching attempts of South Africa. Duane Vermeulen has his hands on the ball, feet widely spread creating a solid base and has complete control over his body. Wales prop Samson Lee comes in too high and not only does he fail to dislodge Vermeulen from the ball, he simply slides off the Springbok’s back and onto the floor.

This is not an issue endemic to Wales, with many nations, particularly those of the northern hemisphere, struggling to clear out fetchers all tournament long. The contact area is becoming more and more the province of the defending side.

Round twelve, knockout blow South Africa

With Wales punched out, South Africa’s moment came. The constant breakdown steals had been blows to the solar plexus of Wales and the dragon was winded. The Boks bobbed and weaved their way passed the slowing, heavy blows of Wales and landed the perfect counter-punch, hitting the home nation with a haymaker.

The Springboks may have jabbed with Damian de Allende and Schalk Burger earlier in the game, who combined for 40 carries, but when the time for the haymaker came, it came in the form of the peerless Vermeulen.

The number eight had been winning turnovers and bulldozing his way through Welsh tacklers throughout the second half, but it was a moment of guile and skill that ultimately brought Wales to their knees.

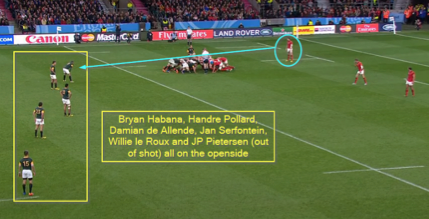

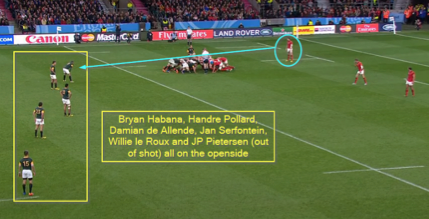

There were just six minutes left to play and South Africa were awarded a scrum deep inside Wales’ 22. The Springboks stacked their entire back line on the openside, even moving blindside winger Habana to a position more or less directly behind the scrum. Cuthbert, Habana’s opposite number, kept his eyes on Habana throughout and shadowed the Bok’s position.

Vermeulen picked and went from the scrum, swatted aside the attempted tackle of the Welsh scrum-half, put a fend on Cuthbert and made one of the most sumptuous backhanded offloads you will ever see to the careening du Preez, who was able to win the race to the try line.

It was a blow which sent Wales to the canvas. Time was running out and though Wales managed to launch a foray into Springbok territory, they were once again unable to stop the defensive pilfering of the South Africans, with de Allende this time getting his hands on the ball at the contact area.

Wales have been a spectacular credit to this RWC with their endeavour and ability to fight through adversity, but this proved to be their ten count. Following Biggar’s try, every combination they threw was not only repelled by South Africa, but also countered. Wales had to make 197 tackles to South Africa’s 123 and it finally told, as the Springboks floated like a butterfly and, finally, stung like a bee.

The Welsh dragon has been battered and bruised over the last month and a half, but they head back across the bridge with not only their pride intact, but also having won the begrudging respect of all four corners of the rugby world.

![George North [left] recently announced his retirement from international rugby George North backs Warren Gatland to continue coaching Wales](/images/c-037703/wales-v-fiji---rugby-world-cup-france-2023.jpg)